There’s no escaping the hype around this one: Dalí at K11 is a big deal. But if it’s oohing and aahing over iconic painting after iconic painting you’re after, this isn’t the show for you. The exhibition focuses on Dalí himself: media darling, sought-after cover star, guest editor and art director for an astonishing range of publications, and above all, an artist who unflinchingly lent his name and style to commercial endeavors spanning everything from cars to cosmetics. That in itself makes the show's venue -- art mall K11 -- something of a perfect fit, and adds a whole lot of depth to the flag-bearer of Surrealism and master of self-promotion. All in all, it’s a really strong show that reveals a lesser-known side of this superstar artist. Full of surprising, small-scale cuttings and covers, if it’s an insight into the cult surrounding Dali, his sheer reach, celebrity and influence you’re after then you’re in for a treat. But if you’re simply hoping to catch in-the-flesh paintings of the same limelight-stealing icons rehashed in books, online and probably a fake exhibition or five, you might be disappointed. Something to bear in mind, for sure. Overall, though, thumbs up.

Dalí: Master of Self-Promotion

Co-organized by the K11 Foundation and Spain’s Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, the show underlines Dalí’s incredible dexterity and celebrity status. All wide-eyed and pointy mustached, his face was everywhere for a time: superimposed onto Mona Lisa for German mag Der Spiegel in 1959, splashed across Photo Monde and Revista -- even looking young and fresh-faced on the cover of a 1936 issue of Time. Viewed all together like this, he makes today’s "celebrity" artists -- the Tracey Emins, Damien Hirsts, or Ai Wei Weis of this world -- look like minor characters. Of course, it’s not just his character, antics, and proclamations that intrigued. His paintings, sculptures and designs remain perennially popular. Classic. For the Foundation charged with protecting Dalí’s estate, that’s a decidedly mixed blessing.

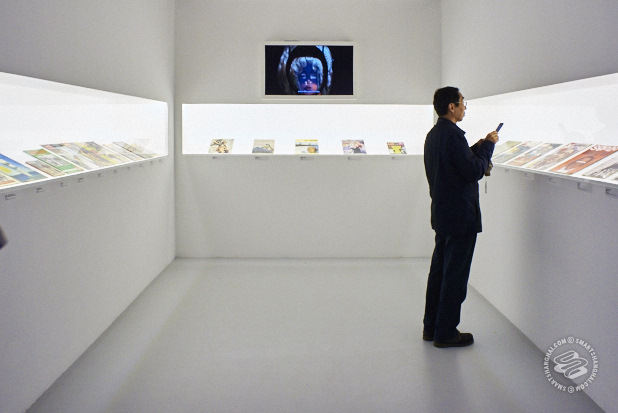

Anyway, magazine covers and excerpts are the mainstay at this exhibition, including those designed by Dalí himself, reproductions of his works or images, or Dalí-created advertisements for everything from Elsa Schiaparelli’s groundbreaking fashions to Perrier water.

Does Dalí’s huge body of commercial work make him a sell-out? Certainly not, explains exhibition curator, Montse Aguer:

"Dalí was very intelligent. He defined himself as a thinking machine and gave us this image of 'showman,' but that’s not real. He arrived in the US in the '40s while a World War was happening in Europe, thinking this was the center of the world -- 'I need to self-promote, I need to help audiences approach my art.'"

Dali’s Legacy in China

From here, things take a turn for the contemporary with a group show curated by LEAP magazine’s Robin Peckham. The first half of this features slightly older, established contemporary artists, and the second is given to younger talents whose connection to the theme feels somewhat shakier.

Of the first bunch -- Zhou Tiehai, Zhang Enli and Wang Xin Wei -- it’s Tiehai’s pleasingly ridiculous Louis XVIII that resonates most with the superstar next door. Peckham explained:

"Looking at their work, what’s shared is humor. All of these painters are very, very funny, which is something you don’t see in a lot of more standard Realist Chinese paintings… what you get from Dalí is this idea of painting as performance… and part of a fundamentally humorous conversation. With the younger generation, there was no interest in Surrealism whatsoever. So we went in and said, alright, despite the fact that they’re disavowing Surrealism, where can we see the legacy of Dalí in their work? The answer was to find the idea of the surreal, the territory between the real and the unreal that’s becoming an interesting place for artists to work in, either because of the media they’re working in and its digital, virtual appearance, or psychology."

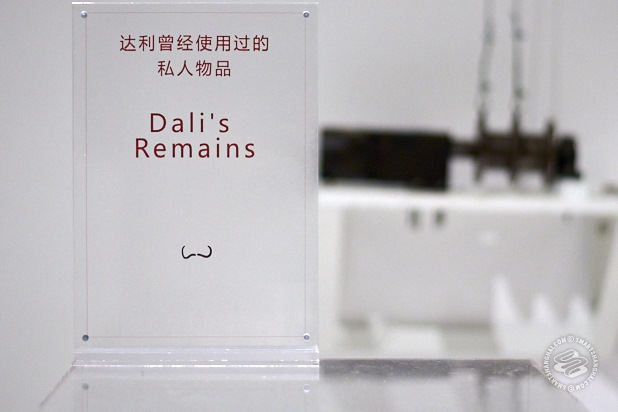

On Repros, Fakes and Copyrights

In the run up to the show, much was made of the fact that this is the "the only exhibition in China showcasing Dalí’s works to be officially authorized by the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation since 2001." Further underpinning these very vocal proclamations of authenticity, certain repros are labeled “First Complete Authorized Replica in Mainland China.” To find out what that’s all about, I asked Joan Manuel Sevillano Campalans, Managing Director of the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation to outline its role with regard to the artist’s legacy.

"Very simply, the Foundation are the right holders. It was the Spanish people who inherited Dalí and the Spanish government who was empowered to manage all copyrights, moral rights, intellectual copyrights -- just as it was doing when Dalí was alive. In order to copy a work, reproduce, adjust or manipulate a work you need the permission of the artist or the right holders, which is usually the family. Dalí had no family; the Foundation was his family. So anything that does not have our permission is not authorized."